Susan (not her real name) first heard the term irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in her 30s when she saw a gastroenterologist about her frequent bouts of abdominal pain and digestive discomfort. He explained to her that IBS was a term doctors used when there was no better explanation for the symptoms she described. She took that to mean there was little that could be done, and she resigned herself to living with pain and discomfort.

Over the next 30 years, Susan consulted various doctors, especially when the pain was severe enough to send her to the emergency room or she experienced diarrhea that was erratic enough to prevent her from leaving home. She tried every available prescription medicine and even underwent CT scans and a capsule endoscopy, but nothing produced answers or relief.

Finally, Susan asked her gastroenterologist whether diet might play a role, and she remembers him saying, "Sure, you could try a low-FODMAP diet."

FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in certain people and cause gas, abdominal distention, and pain.

Although another doctor had mentioned this diet to Susan years earlier, she had found it very hard to follow. However, after years of suffering, she tried it again and was impressed by the results. All her symptoms disappeared within a few days. For the first time in decades, she had a "normal constitution."

This is a common scenario, says Kristi King, MPH, RDN, LD, CNSC, senior pediatric dietitian at Texas Children's Hospital. "Often, patients with IBS make the initial connection between their symptoms and offending foods themselves and then go on to seek help from specialists."

Unfortunately, many clinicians are either unaware of the potential benefits of this dietary intervention or are more comfortable with the traditional pharmacologic approach of treating IBS.

"Raising awareness about the low-FODMAP diet among both clinicians and patients is very important because the two approaches can work together and are not mutually exclusive," King says.

The Birth of a Dietary Intervention

The low-FODMAP diet was "born" in Australia in 2010 when a group of researchers at Monash University found that restricting foods high in FODMAPs could bring relief from common IBS symptoms—abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, diarrhea, and constipation.

The science behind this dietary approach is very robust and includes multiple randomized controlled trials that compared the low-FODMAP diet with various other interventions in patients with IBS, explains William D. Chey, MD, Nostrant Professor of Gastroenterology & Nutrition Sciences at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

"The bottom line is that when you look at the data through a meta-analysis, such as ours,[1] they show that the low-FODMAP diet offers greater benefits than these comparators," he says. "The only randomized controlled trial from the United States was published by our group and has shown that the greatest benefits [of the diet] are for pain and bloating."[2]

"As many as 70%-80% of patients with IBS may benefit, to a certain degree, from the low-FODMAP diet," says Eamonn M. Quigley, MD, director of the Lynda K. and David M. Underwood Center for Digestive Disorders at Houston Methodist hospital. However, he notes that "it is challenging to implement because it excludes many nutrient-rich foods, as well as foods that serve as substrates for beneficial gut bacteria."

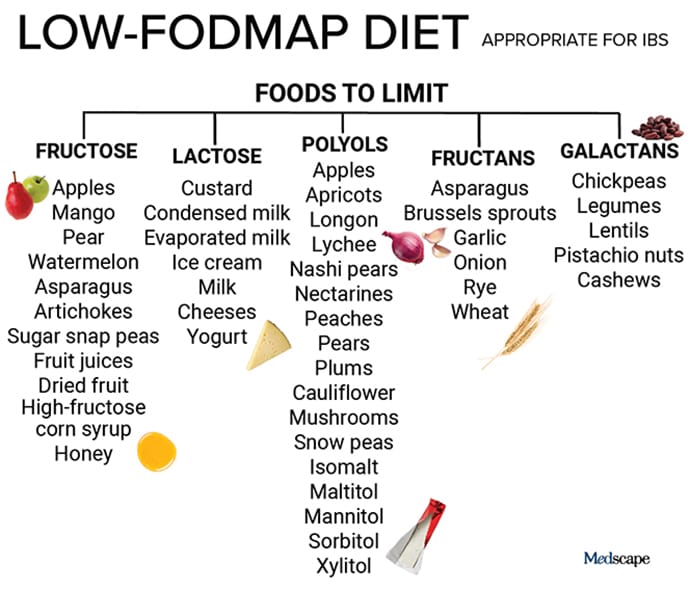

Examples of foods not allowed on the low-FODMAP diet include wheat, rye, onions, legumes, and garlic, which are rich in oligosaccharides; dairy products rich in lactose (a commonly known disaccharide); and fruits with high fructose content, as well as fruits, vegetables, and artificial sweeteners that are high in mannitol and sorbitol (Figure).

Figure. Key examples of foods to limit on a low-FODMAP diet.

"When the sugars contained in these foods start to ferment, they pull extra water into the lumen of the small intestine, causing increased cramping, stomach pain, gas, and diarrhea," says King. "By consuming a low-FODMAP diet and then gradually reintroducing FODMAPs, you can better identify which foods are your trigger foods—those that your body has difficulty digesting," she adds. King emphasizes that this dietary approach is designed to help minimize the troublesome symptoms of IBS and not to cure the condition.

In addition to their osmotic effect, FODMAPs serve as substrates for colonic microflora and produce gas upon fermentation. They are poorly absorbed in the small intestine, so the extra gas and fluid cause distention of the colon and sensations of bloating and abdominal pain. Consequently, the contraction of muscles in the wall of the bowel is affected, which may lead to increased peristalsis and diarrhea in some patients or constipation in others.

A Personalized Dietary Protocol, Not Just a Diet

Chey explains that the low-FODMAP diet is really a three-phase dietary protocol consisting of a 2- to 4-week FODMAP elimination phase, followed by a gradual reintroduction of foods containing individual FODMAPs to determine patient sensitivities, and then liberalization of the diet in the final phase.

"Usually, patients who are going to respond will get better within a period of 2 weeks, but it can sometimes take up to 4 weeks for some to see the benefits," he says. "The patients who do not respond within the 2- to 4-week time frame should be advanced to some other form of therapy. Of the patients who do respond, approximately 85% or more are able to liberalize their diets over the long term and make them less restrictive."

King says that the situation in pediatric patients is similar. "In our clinical experience, we found that within 2 weeks, either patients improved or they did not. If there is no improvement within 6 weeks, I recommend talking to the healthcare provider and transitioning back to the regular diet."

According to Chey, the low-FODMAP diet can also be beneficial for other GI conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

"We are increasingly using [this diet] in patients who have IBD and are in remission in terms of inflammation but still have symptoms, such as abdominal pain and altered bowel habits," he says. "Again, the symptoms that are most likely to respond to this diet are pain and bloating. Some patients will also experience benefits with respect to diarrhea, but we found that this is not as consistent or reliable."

Taking Things Too Far

All three experts agree that obtaining guidance and supervision from a dietitian familiar with the low-FODMAP diet is critical to the success of the intervention and safety of the patient. To supplement that, Monash University recently developed a FODMAP diet app that provides recommendations about the foods patients should eat—and those that should be avoided—while on the diet. Other online resources are available for patients, dietitians, clinicians, and researchers, including a guide to help patients successfully facilitate the diet.

"The low-FODMAP diet is a complex protocol that has a strong educational component and requires guidance from a dietitian who will make sure patients are compliant with the exclusion phase and [ensure] their diets are medically and nutritionally responsible," says Chey. "The reality is that if you leave this entirely to patients, they may go on a low-FODMAP diet that may not be nutritionally complete."

King notes that a poorly implemented low-FODMAP diet can lead to deficiencies in vitamins, minerals, and protein. She also stresses that the systematic way of reintroducing FODMAPs in the second phase of the protocol is very important and cannot be done properly without expert guidance.

"The reintroduction phase is critical," she says. "Typically, we will give patients one serving from one FODMAP group for 3 days in a row, followed by a washout period of about 1 day. If the patient does not experience any symptoms during the 3 days, we will try to introduce a food item from group 2 after the 1-day washout period. The washout period can sometimes last longer, up to 5 days, depending on the individual patient and whether they experience symptoms. So, this process is very systematic, and it takes time and energy to determine each patient's trigger foods."

Beyond nutritional deficiencies, if not properly supervised, a low-FODMAP diet can lead to other complications and additional health issues. Quigley warns that patients can develop psychological problems that include obsessions with what and how much they eat.

"There is a danger with all of these strict dietary approaches for people to develop an almost pathologic obsession with their diets that can become injurious to their health," he says. "One has to be careful in monitoring the patients on any diet, including the low-FODMAP diet, to make sure their nutritional status is maintained, and this is best achieved by working with a dietitian."

As with antibiotic overuse, microbiome dysbiosis can result from an overly restricted diet because the composition of the gut microbiome is largely determined by the availability and competition of various substrates. Many foods that are restricted on the low-FODMAP diet, such as garlic, onions, and asparagus, are great sources of prebiotic fibers that play an important role in balancing the composition of the gut microbiome.

Regarding microbiome dysbiosis, Quigley says that "there is some evidence that providing probiotic supplementation to patients who are on the low-FODMAP diet may correct some of the deficiencies in the microbiome, but we don't know yet whether that has any health implications."[3]

The Importance of a Holistic Approach to Treatment

In managing patients with IBS, and also IBD, experts believe that clinicians should use all the tools available to them. This includes combining integrative medicine with standard pharmacotherapy.

"It is increasingly becoming apparent that an integrative, more holistic approach is needed in caring for these patients," says Chey. "Such an approach, which may incorporate diet, behavioral techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy or hypnosis, and medications, should be tailored based on patient symptoms and preferences. We often utilize a multimodal approach in patients with IBS that combines medications with diet and behavioral interventions."

As far as the low-FODMAP diet specifically, Chey says that a recent study[4] conducted by his team has shown that it led to significant improvements in both quality of life and anxiety compared with the usual dietary recommendations. "We've shown that as GI symptoms get better, quality of life and anxiety get better."

In fact, the University of Michigan, where Chey practices, implemented one of the first GI dietitian programs in the United States in 2008, and it continues to be a hub for clinicians and patients interested in learning more about the benefits of dietary interventions for GI conditions.

King recommends that clinicians and patients visit FODMAP Everyday and use the resources pooled by IBS expert Kate Scarlata, RDN, as well as connect with a local registered dietitian through the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics website.

King also notes, "Addressing the symptoms of IBS early in the course of the disease using the low-FODMAP diet may spare patients from resorting to more aggressive pharmacotherapy and continuing discomfort associated with the condition."

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Gastroenterology © 2019 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: The Low-FODMAP Diet for IBS: What You Need to Know - Medscape - Aug 23, 2019.

Comments