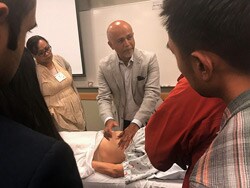

Dr Abraham Verghese did not become famous for performing physical exams, but when he places his hands on the abdomen of a standardized patient in a teaching hall, a crowd quickly forms. The learners watch intently as he palpates the area.

"Let the spleen come to you instead of the other way around," he says softly, heads bobbing in acknowledgment.

Dr Abraham Verghese

Dr Verghese is a best-selling author and recipient of a National Humanities Medal for his contributions to literature, but in this space, it's his medical prowess and approach to patient care that invite admiration. Many people who work with him describe him as the model of a caring physician.

"Very often, at the end of a physical exam, I am told two things," Dr Verghese says. "One: 'I've not been examined this way before'– which, if that's true, is a real condemnation of our system.

"And then, surprisingly, I find that I can tell [patients] exactly what they heard elsewhere: 'This is not in your head. This is real, but the good news is that it's not cancer or tuberculosis, or whatever. The bad news is that we don't know exactly what's causing this, but here's what we should try to do.'

"And I always feel that, if I get the buy-in, it's because something happened in the exam."

His appreciation—almost awe—of the patient physical exam has spawned several initiatives at Stanford University, where he teaches. Most recently, it was the centerpiece of a weekend symposium that attracted residency program directors, chief residents, and other clinicians from across the country who wanted to improve their own bedside exam skills and then teach others at their own institutions.

The annual symposium includes discussions about the importance of patient exams as well as hands-on tutorials of the essential exam techniques called the "Stanford 25," which range from hand exams to gait abnormalities.

"There's a meaning that's enacted, even if there's nothing of relevance that's going to come out of the exam," Dr Verghese says. "Even if none of these things 'pan out,' you will have gotten the buy-in to be able to say, 'No, you don't need a CT scan, we don't need the neurology consult; let's just watch this and see each other in 3 weeks, and then let's go from there.'

"That's priceless, you know?"

It's obvious that Dr Verghese has a special place in his heart for patients. His own mention of Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich brings tears to his eyes. (He describes it as "the most profound description of what it is like to be ill.")

But he has a similar ache for clinicians who are experiencing burnout at epidemic levels, and he's an outspoken critic of the electronic medical record (EMR), which he believes has driven a wedge between physicians and patients.

"Meaningfulness in this profession comes from one-on-one interactions with patients," Dr Verghese says. "The moment you feel like you're just another widget, it just takes the soul out of many physicians' lives."

As physicians have seen their connections with patients weaken, they have become more isolated and have lost the joy in delivering patient care, he says.

"I think we've worked harder in previous times; we've had longer hours in previous eras," he muses. "We've been exposed to more dangers directly, from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), tuberculosis, smallpox, etc, but I don't think we've ever had a point in time where physicians felt that meaning had eroded as much as they do now."

Although he is critical of EMRs, he is not anti-technology. In fact, the promise of artificial intelligence (AI) has captured his enthusiasm.

"Physicians are totally frustrated, because every measure of how they do is based on how they enter things in the computer," Dr Verghese says. "AI has a great potential to change that."

He recalled his own recent visit to a doctor who used Google Glass to record the entire exam.

"It was the first time that I felt that neither of us was distracted by this third party!" he said.

If AI systems are able to perform tasks such as record keeping for billing purposes, it could leave physicians free to focus on what they really want to do: provide patient care.

"The moment we can separate [billing] from the true record keeping, we'll make a lot of progress," Dr Verghese says.

Physicians need to start a "revolution," he suggests, to demand the resources needed to restore patient care, and he's optimistic that they will succeed.

"I mean, a hospital administrator who has to deal with 50% of their physicians being burnt out and depressed—that can't be good," he said. "I think that if a physician says, 'You know what, buy Google Glass or we're not going to be able to do this anymore,' they will buy Google Glass. They will do whatever it takes!"

In Dr Verghese's "utopian vision" of the near future, doctors will be able to focus on "making sure that what's plugged into the AI machine is based on an accurate interpretation of what patients are saying and what we're seeing," rather than on actual data entry, which, in its worst form, involves copying and pasting information that was not gathered during the actual patient exam.

In the current world of reality television and social media, physicians today often miss what is really going on with patients, Dr Verghese says.

"How is it that, in a postmodern society that has People magazine and all of this crap out there that indicates how flawed we are as human beings, how complicated we are, how rich our emotional lives are—how is it that in medicine we can feel that it's not important?"

This disconnect may explain the rising popularity of acupuncturists, massage therapists, and other "healers."

"They do one thing that we don't do well: they touch," Dr Verghese says, adding that his own personal experience bears that out. When he experienced back and neck problems, he saw many specialists, from surgeons to neurologists to pain specialists. But the strongest connection he felt was with the physical therapists and massage therapists.

"They were the only ones who really examined my body," he said. "The others were more comfortable with the image or the representation of the disease."

Competency in performing physical exams is a prerequisite, Dr Verghese notes, which is why he is committed to programs like the Stanford 25, a set of skills that are taught not just in occasional symposia but year-round to medical residents training at Stanford. But mastering those skills is just the beginning of true bedside medicine.

"You can't make this a decision tree," he says. "It's more than that; it's the art and science of medicine. It's a human experience."

Another project of his called, simply, "Presence" focuses on that human part of medicine. An introduction on the site explains the foundation of the program:

Being present is essential to the well-being of both patients and caregivers, and it is fundamental to establishing trust in all human interactions. Being present is integral to the art and the science of medicine and predicates the quality of medical care.

In his own words, Dr Verghese explains how this focus can transform patient care.

"We [as patients] aren't just coming to the hospital for a peptic ulcer; we are coming to the hospital with a peptic ulcer in the setting of a terrible marriage, and the kid who is driving us crazy, and God knows what else."

For physicians who have lost that vision, recovering it may take some soul-searching, and Dr Verghese strongly recommends reading the Tolstoy classic he loves as well as other inspiring works. His own books have proven inspiring for many other physicians, especially the bestseller Cutting for Stone.

Another renowned author, Siddhartha Mukherjee, once told Medscape that he recommends an earlier Verghese tome, the nonfiction book My Own Country , which describes the early days of the AIDS epidemic in rural Tennessee, where he was practicing.

"Verghese's portrait of these patients is intimate, compassionate, and unforgettable," Dr Mukherjee said.

Fans of Dr Verghese as author will be happy to hear that he is working on another novel, this time about a spinal surgeon who is "making the crooked straight."

A common thread running through all of his work, on the page or at the bedside, is a love of medicine, gratitude for his role as healer, and faith in the medical profession.

"My operating philosophy is to remind ourselves, 'We're getting to do this. It's not that we have to do this—we get to do this,'" he says. "It's a privilege."

Follow Christine Wiebe on Twitter @CWiebeMedscape

Join Medscape on Facebook

Medscape © 2017 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Abraham Verghese: 'Revolution' Starts at Bedside - Medscape - Oct 24, 2017.

Comments