Photo by Darbe Rotach

Dr Richard Isaacson is the first to admit that he is a terrible cook.

The Cornell neurologist, a dementia expert, is more of a takeout guy—but a takeout guy with enviable discipline when browsing a restaurant menu. Faced with minimally effective treatments at best and a recent trail of disappointing drug trials, Isaacson is among a growing cadre of doctors turning to lifestyle interventions to prevent or slow the onset of Alzheimer's disease. And nutrition, he feels, can be integral in doing so, particularly in people like himself with a family history of the disease.

Isaacson founded the Alzheimer's Prevention Clinic at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian in 2013. It was the first medical center in the country, and perhaps the world, dedicated to dementia prevention as opposed to just management. The clinic's mission is to catch people at risk for Alzheimer's years before symptoms would normally arise and to intervene with personalized prevention approaches. By analyzing and addressing a complicated tangle of family history, biomarkers, and lifestyle factors that may predict an increased risk, Isaacson is seeing real results.

The clinic is housed in a slender building tucked away between a bodega and an apartment building on New York City's Upper East Side. I arrive around 9:30 on a chilly Thursday morning in March, after an eternally delayed subway ride. A few minutes later, Isaacson strides in.

"How was your commute?" I ask.

"Quick," he answers with a muted New York accent and a grin. "I chose hospital housing, and my apartment is as close as you can possibly get to the clinic."

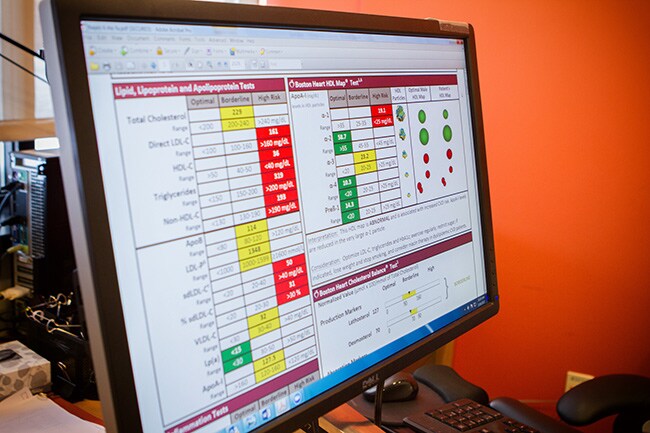

We shed our coats and sit down in his consultation room. "Look at this," he beams, pointing to his computer screen. A recent patient lab report reveals a complex breakdown of cholesterol subtypes—and also insulin levels, adiponectin levels, and hemoglobin A1c status. It seems more the health record of a cardiology patient, not of someone being seen by a dementia neurologist.

Dr Isaacson walks us through his typical patient assessment.

Photo by Darbe Rotach

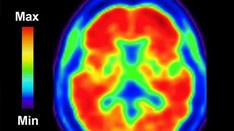

Like heart disease, neurodegeneration typically doesn't surface overnight. Pathologic changes in the brain can begin 20 or 30 years before Alzheimer's becomes symptomatic. Roughly 400 of Isaacson's 600 clinic patients are seen exclusively for prevention, the majority of whom have no symptoms at all. "A lot of my patients are in their 30s and 40s, and my youngest is actually 27," he says. "But I'll admit that any younger than that, and I'm not quite sure what to do."

When Isaacson isn't traveling to lecture, overseeing a residency program, or visiting his fiancé, an ophthalmology resident in Los Angeles, he is usually seeing patients. He starts by screening them for dozens of risk factors associated with Alzheimer's dementia: Impaired glucose metabolism, excess visceral fat, inflammation, and elevated homocysteine are just a few.

Some associations have not necessarily been widely reported on in the literature. For example, Isaacson has observed that small, dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol particles—known to be proinflammatory—are associated with impaired executive function. He now often orders cholesterol fractionation testing on his patients.

A patient health record reveals cholesterol fractionation testing results.

Photo by Darbe Rotach

"I'm a clinician first, and I see patterns," he says. "It only takes 20 or so patients to say, 'Hey, your executive function is impaired, and your particle size is worrisome. Maybe we should try cholesterol modification.'" Isaacson is, however, launching a pilot trial exploring the link between cholesterol subtypes and dementia risk; and plenty if not most of the interventions he considers are evidence-based—interventions like exercise, improving sleep health, encouraging socializing, and treating hyperinsulinemia.

He is also a big proponent of Mediterranean-like diets in helping fend off Alzheimer’s. A growing body of observational data links diets centered around healthy fats, vegetables, and whole grains with improved brain health, especially when combined with other lifestyle factors.

Isaacson cites the FINGER trial,[1] published in the Lancet in 2015. This large, 2-year study found that a combined regimen of a brain-healthy diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring helps improve or maintain cognitive functioning in elderly people at risk for Alzheimer's. Similarly, preliminary data from the MAPT trial[2] suggest that supplementation with the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid—or DHA—combined with cognitive interventions and exercise for 3 years can improve cognition.

But then there are the unmodifiable Alzheimer’s risk factors to consider, namely family history and our genomic luck of the draw.

A year or so ago, Isaacson began suggesting that his patients undergo gene sequencing and share their results. He first looks for variants of the APOE gene that are known to increase Alzheimer's risk, including the APOE4 allele, which is carried by around 20% of people. Having one copy of APOE4 can double Alzheimer's risk; having two results in a 12-fold increased risk.

Isaacson also screens for a bevy of less common genes associated with many forms of dementia. When taken together with clinical and lifestyle risk factors, he can come up with an overall risk profile for each patient and better customize care. Research[3] by Isaacson and colleagues presented at last year's Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease meeting shows that the effectiveness of certain prevention interventions is greatly influenced by each patient's genetic profile.

"We're figuring out how all these genes and factors interact together to influence the chances of getting Alzheimer's. Then we can more accurately determine which interventions might work in which patients," he explains while calling up another patient report. "She has a mutation in the TNF gene that can increase risk—up to 6.6-fold if she also has APOE4. Should I be treating her with an anti-TNF drug or an anti-inflammatory? Maybe. This is the kind of thing we're trying to figure out."

Medscape Neurology © 2017 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: One Doctor's Mission to Personalize Alzheimer Prevention - Medscape - Mar 31, 2017.

Comments