A few years ago, I overheard a surgeon lamenting the consultation-notification process. He complained that the initial information given often affords little opportunity to prioritize. On busy mornings when consults are dealt like cards at a poker table, accurate information is vital for triaging a complicated schedule. The surgeon's commentary, laced with a few expletives, brought to mind the worst communicated consult request of my entire career. It highlights how too many screens, too little conversation, and the ever-changing number of players on a patient's team can muddle both the history and clinical status reports.

That Saturday morning, I got out of the shower a total of three times to answer calls from the hospital. I silently cursed Steve Jobs, rest his soul, as my slick fingers slid across the unlock mechanism to no avail. I grabbed a waiting Kleenex, redried my hand, and tried again successfully.

"Dr Walton-Shirley," the anxious voice said at the other end, "we have a cardiology consult for you."

"Ok. Whatcha got?" I asked, thinking my exuberance might conceal the fact I was in my bathroom with water pooling at my feet.

"Leuko-cy-ti-osis," the voice said, laced with uncertainty.

"I'm happy to come to see the patient but that's not a reason for a cardiology consult," I said. "Perhaps I should speak to the nurse?" I asked extra kindly.

"Sure. I'll get her," the voice agreed.

A long 90 seconds or so pass. . . . before the nurse arrives.

"I'm happy to help you, but can you give me a hint about what's going on with your patient?" I asked.

"It's a preop," said the nurse happily.

"I appreciate that, but that still doesn't tell me why a cardiology consult is being called. I've received three consults in about 20 minutes and I need to prioritize, so can you tell me a little about your patient?" I asked again.

Silence for about 15 seconds.

"Well . . . it looks like it's a shoulder fracture," she said finally.

"Okay," I commented, subconsciously searching the deep recesses of my neuronal polite connections. "But that still doesn't tell me why there is a cardiology concern," I added, with my hair dripping onto my smartphone, which has never learned to swim.

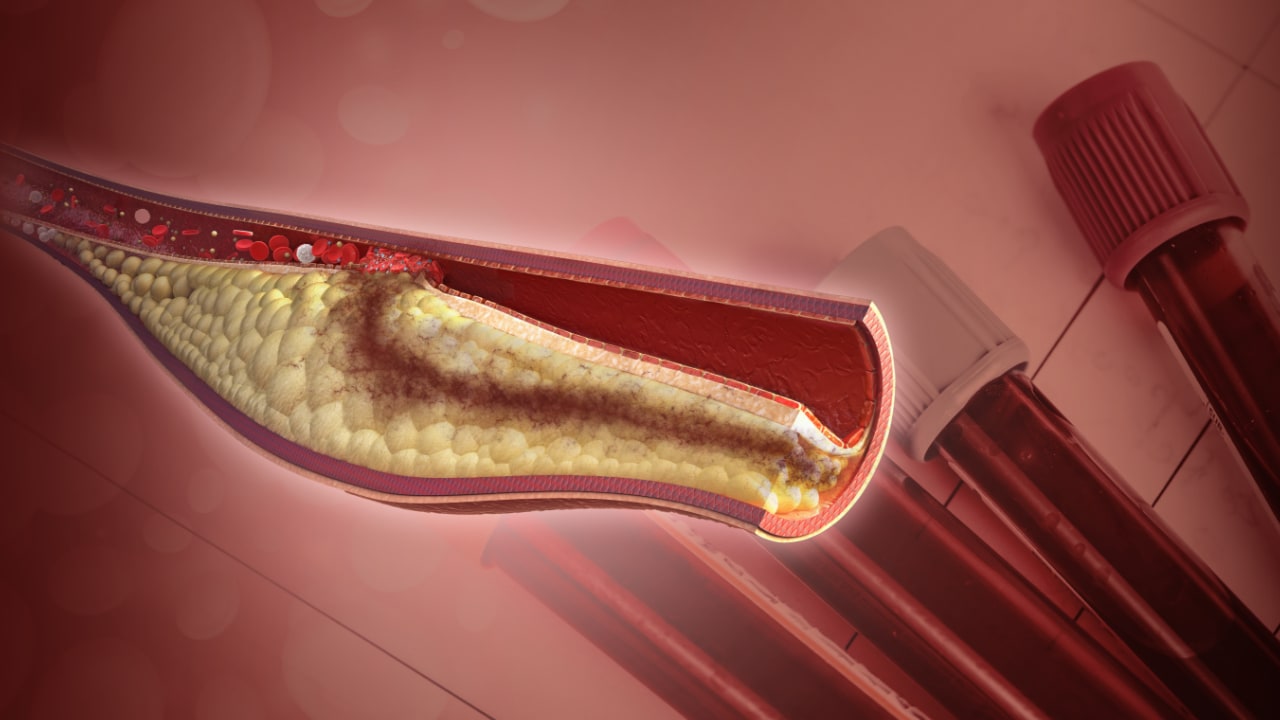

"Well, you're right," the nurse said with a nervous chuckle. "Let me see if there is any reason why they might want a cardiology . . . consult . . . hmm (I hear pecking on a keyboard . . . more pecking . . . more pecking . . . ). "Okay. It says here . . . that she has inoperable coronary artery disease," she concluded with a hint of relief and glee intermingled.

"Bingo," I said. "Do you know what time they are going to the OR?" I asked, thinking I might get a direct answer.

"I have no idea," the nurse said. "But I can find out," she offered.

"Not necessary," I answered. "I'll just make your consult first. I'll be there in about 30 minutes."

When I entered the ICU, I checked the history and physical recorded in the record. Indeed, the note dictated the night before mentioned last year's "cardiac arrest with known inoperable coronary artery disease." The ECG was normal, troponins were normal, and her vital signs were stable.

The patient's husband was at the bedside. She was lethargic and answered "yes" or "no" inconsistently, submerged in the sweet haziness that only an alphabet soup of narcotics can afford. I completed the exam, discussed the requested tests, and promised a longer look through the historic record. I told her husband that "it will be a high-risk procedure given her prior history," but we would "do our best." The husband thanked me, and I returned to the desk to roll up my sleeves on the medical record.

I sat down behind the nursing desk feeling pretty good about the conversation with the husband until I finally received the cath report from an outlying hospital of her "normal coronary angiogram." I then located a "normal" regadenoson pharmacologic challenge in the preceding 6 months. I found some information regarding the "cardiac arrest," and it wasn't technically cardiac. (If I tie a plastic bag around your head and wait long enough, your heart will stop, but that doesn't mean it's cardiac in origin). She had aspirated, for reasons I still don't understand, became hypoxic, and required CPR but had a normal ventricle, angiogram, and even a normal stress exam. I then noted the "no-code" status at the top of the page, and my heart sank.

I sheepishly went back into the room to discuss all the information I'd found. I gently asked if the DNR status was because she was under the impression she had a "bad heart." The husband, obviously shocked at the 180o change in cardiovascular prognosis, thankfully said, "No." He explained that during CPR, they broke her ribs and she had a very hard time for weeks after that. She didn't ever want to go through that again.

Despite the fact that the patient and her family had seemingly made the right decision for the right reasons, the wrong consultant had been called for all the wrong reasons. My only role was to get the words "inoperable coronary disease" off the list of diagnoses in a patient who had never had coronary heart disease, but it will probably never be expunged from the medical record. I hoped that at the very least it didn't make the list of discharge diagnoses and that the next person would actually read my consult.

As a modern-day cardiologist, I've added detective and scribe to my résumé with no formal training in either profession. Until medicine can straighten out the mess we've made of documentation, we'll have to wear as many hats as it takes to protect our patients. I wrote about this case to highlight the need to figuratively wrap yellow caution tape around every recorded history and physical. It's always prudent to initially declare every new patient guilty of having heart disease until proven otherwise, but in every instance, we need to work harder to find the truth and to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth when we do finally find it, so help us God.

Cite this: Melissa Walton-Shirley. The Cardiac Consult That Wasn't - Medscape - Apr 20, 2017.

Comments