If you believe machines will soon surpass human intelligence, do not cite the computer's ability to read a simple 12-lead ECG. Multiple studies confirm the unreliability of computer-reads of the ECG.[1,2]

But that is not the big story.

The big story is the marked rise in fake atrial fibrillation (AF) and other faulty ECG interpretations. Fake AF occurs when the computer calls the rhythm AF, the doctor believes it is AF, but it is not AF.

My cardiology colleagues and I are seeing many more of these fake arrhythmias. Sadly, patients are being treated for conditions they don't have.

Clinicians' growing reliance on imperfect ECG-reading algorithms is dangerous because the pattern formed from the 12 leads of an ECG contains vital information—myocardial injury, ischemia, heart block, QT prolongation, etc. Said simply: ECGs are serious business.

I write this column for two reasons. One is to better understand the clinician's relationship with technology; and the other is to alert you to a patient-safety issue—one that is not getting enough attention.

Fake AF and Missed AMI

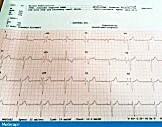

"Fake" atrial fibrillation. Computer reads AF despite easily visible P waves. Image courtesy of Dr Mandrola [to view a larger image, click here]

Here are representative cases, the first two resulted from computer overreads and the third was an underread. (I have many more cases.)

A patient with atrial fibrillation taking an anticoagulant for stroke prevention suffered a major bleed from an ulcer. This person did not have AF; the computer mistook his PVCs and low-amplitude P waves for AF. The doctor prescribed anticoagulation based on the computer-read.

A middle-aged man was diagnosed with AF during a yearly visit with his primary-care doctor. He took medicine and worried about his health for 2 years. Only he did not have AF. The computer misread the ECG, and again the doctor acted on the computer's call.

A young patient suffered heart failure after a delayed diagnosis of acute MI. The initial ECG revealed only subtle hyperacute T-wave changes and the computer did not call it. Neither did the doctor. (My hunch is that the EMTs' and doctor's eyes were drawn to the "normal ECG" computer-read.)

I think I know why this problem is getting worse.

In the really old days, say 25 years ago, ECGs did not come with computer-reads. The ECG included only the raw data, the electrical signals. This meant doctors at the point of care had to look at the actual tracing and interpret it in the setting of the patient's story.

Expert ECG readers then passed this knowledge along to students and nurses and technologists. The result was that most clinicians knew how to recognize AF and other important patterns, such as MI and QT prolongation. The diffusion of ECG-reading skills was a form of "herd knowledge."

Computer readings of the ECG have gradually eroded knowledge of the herd. Decades ago, when computer-reads were first added to ECGs, readers knew to look away from the computer's call and see the actual signals. Over the years, however, the eyes and brains of clinicians have been drawn to the computer-read.

Clinicians may know the limits of the computer-read, but for some reason, the person at the point of care believes the computer more than their own eyes. I've seen faulty computer reads actually make it harder for the reader to interpret the pattern. Instead of seeing the clear P waves, the reader searches for AF because that's what the computer called.

In Streetlights and Shadows,[3] research psychologist Gary Klein describes four types of decision-support systems:

The decision is made by the decision maker alone.

The decision-maker is aided by an algorithm.

The decision-support system has the final say with inputs from the operators.

The decision-support system makes the entire decision on its own—as in an antilock brake in your car.

The first two categories are where we should be with ECG reading. Instead, too many clinicians are ceding the entire decision to the faulty decision-support system.

I can only speculate why we trust the computer to read an ECG. Perhaps we've grown comfortable with the computer controlling many other parts of our lives (GPS systems, Siri); perhaps clinicians feel the ECG readings have been vetted and wouldn't be allowed if they weren't reliable. That's actually a good question for policy makers: why, exactly, do we allow computer-reads if they are so lousy?

I am no expert in artificial intelligence, but there are typical patterns of computer ECG mistakes. A common one is when the computer tries to interpret poor-quality tracings. Baseline artifact or poor electrode contact should be a warning not to accept the machine read. Irregular rhythms are another area in which the computer struggles. A tip is to hide the computer read—don't look at it until you have interpreted the actual signals.

For the past few years, I've urged leaders in my hospital and group to turn the computer-reads off. My belief is that clinicians would then have to look at the ECG, and skills would improve. That hasn't happened. To the clinical researchers out there: this could be a great study.

A day may come when we will be able to trust the computer to read an ECG. We are not there yet, not even close.

For your patient’s safety, look first at the signals, reject poor-quality tracings, and know that the computer-read is unreliable.

JMM

Cite this: ECG-Reading: Don't Cede Control to the Machines - Medscape - Apr 06, 2017.

Comments