Bariatric Surgery Patients' Special Requirements

Hello. I am Dr David Johnson, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia. Welcome back to another GI Common Concerns—Computer Consult.

I have seen a lot of blogging back and forth recently with questions about bariatric surgery and, in particular, what to do with these patients. This Computer Consult is meant to tell care providers, irrespective of specialty, to be on the alert when somebody tells you that they have had previous bariatric surgery.

This is now one of the most commonly performed surgeries, not only in the United States[1] but also emerging worldwide.[2] This is due to the obesity epidemic and the significant improvement that we see not only in weight reduction but also in the metabolic consequences, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular risks, and even cancer risk.[3]

In my experience, one of the things that does not happen commonly enough is the routine monitoring of these patients. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now requires you to perform this operation to be a recognized Center of Excellence, and there are certain criteria that equate to this. There are many patients who have had these bariatric procedures who may perhaps just land in your lap. Therefore, you really need to understand that these patients need to be watched routinely.

I have been privileged enough to edit two issues of Gastroenterology Clinics in North America in 2005[4] and 2010,[5] which included work on bariatric surgery. In doing so, I have learned a lot from a lot of smart people, and want to highlight some of the things that are really critical for you to know when you see these patients in your practice.

Macronutrient Deficiency

First, there clearly are elements of macronutrient deficiency. This is protein malnutrition. The worst case is those patients who come in with severe protein malnutrition.

It is important to recognize that the protein malnutrition is maybe a consequence of how they are eating, but also depends on what type of surgery they have had. The more extensive surgeries, such as biliary-pancreatic diversion surgery or more extended Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, may result in more protein malabsorption. You can also see this with bacterial overgrowth.

Routine monitoring of albumin in these patients is pretty reasonable, but prealbumin is probably a better short-term assessment here and more variable in response to interventional nutritional efforts.

Vitamin Deficiencies

The topic of vitamin micronutrients is what I want to spend the bulk of the time on today.

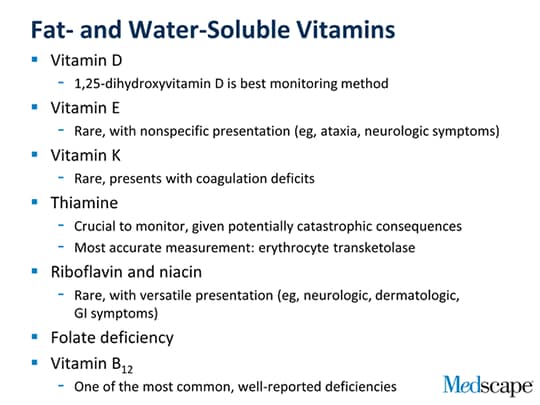

These cannot be synthesized; you have to ingest them. There are fat- and water-soluble vitamins. The fat-soluble vitamins are A, D, E and K, which clearly can be malabsorbed and then manifest as particular disease states.

With the fat-soluble vitamins (eg, vitamin A, keratins), patients may have some common visual symptoms and also some elements of very nonspecific things, such as dry skin, dry hair, and pruritus. Recognize the sublime nature of these types of presentations, and that you really have to be on your toes when you start to assess this.

Vitamin D deficiency is very common after bariatric surgery, and something you have to monitor on a regular basis. In particular, we monitor 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Isolated serum calcium measurements are not adequate to follow these people, who may have a long period where their calcium is actually normalized. Urinary calcium is a good way to measure this, but its excretion can be altered and accelerated by concomitant use of diuretics. If a patient is hypertensive or they are on diuretics for edema, urinary calcium may be increased as well. You really need to follow and monitor total 1,25- hydroxyvitamin D and 24-hour urinary calcium.

Vitamin E deficiency is relatively unusual. When patients present with this, they have very nonspecific features, including ataxia, neurologic symptoms, loss of sensory vibration, muscle weakness, and sometimes even hemolytic anemia. It is very unusual in this patient population, but again, something to be aware of.

Vitamin K is primarily absorbed in the jejunum and the ileum, which are not as extensively bypassable, although the jejunum is considerable depending on the length of the gastric bypass or, in particular, with biliary pancreatic diversion. Patients with vitamin K deficiency may have coagulation deficits. Recognize that vitamin K is very important not only in the development of prothrombin, but also factors 7, 9, and 10, as well as protein C and S. These are things that essentially are required for adequate coagulation. Again, such a deficiency is unusual in the bariatric surgery patient, but must be considered in the appropriate setting.

As far as the water-soluble vitamins, the one that I insist you cannot forget is thiamine. Remember: thiamine, thiamine, thiamine. Vitamin B1 deficiency is potentially a catastrophic complication; it relates to what we see in alcoholic patients with classic Wernicke encephalopathy, but this can be the same presentation in a bariatric surgery patient. There are patients with malabsorption, but there are also those with clinical small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth who are refractory to thiamine repletion and respond to antibiotics directed toward it.

The most accurate measurement of thiamine deficiency is the erythrocyte transketolase measurement. It may not be something that you can whip around in your lab very quickly, but it is the best bioassay. We routinely measure thiamine levels, although the key to remember is that it is whole-blood thiamine, not just serum thiamine. It may be still underrepresenting the thiamine stores, but if you are going to order a thiamine level in these people—and you routinely should—you need to remember whole-blood thiamine. Certainly, when patients present with problems, in particular significant nausea and vomiting, they need to be replete with thiamine.

Some of the other water-soluble vitamins, such as riboflavin and niacin, are very rare deficiencies in this population, but ones that can be very versatile in their manifestations. Patients with riboflavin deficiency may present with stomatitis, anemia, or some scaly dermatitis, whereas in niacin deficiency the classic presentation is pellagra rash. These are very unusual, but they may also involve neurologic; dermatologic; or even some gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting.

Folate deficiency is something that also needs to be considered, particularly in patients with a more extended bypass. Elevated folate levels may also tip you off to bacterial overgrowth, which is a consequence for some patients with bariatric surgery.

Vitamin B12 deficiency has been fairly well described as a nutritional deficiency post-bariatric surgery, given how commonly it can occur. This makes logical sense, because it relates to bypassing the parietal cell mass, which is the site of the R factor and the R intrinsic factor. In addition, you have a relative achlorhydria after bariatric surgery, so some of the oral B12 may not be subject to the de-conjugation process in facilitation for absorption. This is also something that may be complicated with bacterial overgrowth, which can accelerate the metabolism of B12 and allow B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 needs to be monitored routinely in these patients.

Trace Elements

Regarding trace elements, zinc is the one to remember. Zinc, as you know, has a prominent role as a cellular antioxidant. This is something that can cause various symptoms, including skin manifestations, alopecia, glossitis, nail dystrophic changes, classic rashes, and the acrodermatitis enteropathica that you see in severe zinc deficiency.

Iron absorption is obviously a problem, given that you bypass the proximal intestine, the primary area where it is absorbed. These are patients who may have a relative achlorhydria because the gastric pouch does not have much acid. This absorption of non-heme iron from plant sources and bypassing of this duodenum and proximal jejunum may compound the iron deficiency. It is incredibly common, in my experience, and furthermore compounded if patients have some type of gastric mucosal disruption or ulceration. Iron deficiency clearly needs to at least be thought of in this patient population.

Copper is a joint transport mechanism similar to zinc, and copper deficiency really may be a problem. If you are giving your patients liquid vitamin supplements, take note that these may be deficient in copper. This is something you need to watch clearly on a semi-annual or annual basis, in particular after 3 years. Copper deficiency can induce some hematologic and profound neurologic abnormalities.

Zinc, iron, and copper deficiencies must be considered and monitored routinely.

What to Watch Out For

My bottom line is that when somebody comes in post-bariatric surgery, you need to be thinking that every symptom that they report may be a nutritional metabolic consequence.

With something simple, such as anemia, contributing factors run the gamut from deficiencies of iron to vitamin A, vitamin E, folate, zinc, and copper.

I have also seen some profound neurologic deficits, peripheral neuropathy being the most common; these also can be caused by a variety of vitamin deficiencies, such as niacin, vitamin B12, vitamin E, and copper. Also, remember to consider thiamine deficiency, and if you order thiamine levels, assess whole-blood thiamine or the erythrocyte transketolase.

Visual disturbances are something you may not think of asking about, but this is why it's important to include in your checklist that you routinely probe these people about every symptom as it relates to neurologic, visual, and dermatologic manifestations. With visual symptoms, the classic cause is vitamin A deficiency, but thiamine and vitamin E deficiencies can also result in visual impairment.

With skin disorders, think about deficiencies in vitamin A, niacin, and zinc. These are very classically associated with skin disorders and dermatitis.

Final Recommendations

What do I recommend for my patients?

On the basis of the metabolic recommendations from the bariatric surgery societies and national guidelines,[6] it is routine to advise these patients to take a chewable vitamin. I ask my gastric bypass patients to take a chewable vitamin twice daily—not a gummy bear, not a routine swallowed vitamin. A chewable [vitamin] disperses the vitamin and allows for potentially better absorption, within a limited bioabsorptive space. Then I have these patients take 1.2 g of elemental calcium. I personally put them all on 800 IU of vitamin D. If you choose not to do that, you should be monitoring them on a regular basis.

This is a proactive routine that should be coordinated by the surgeon, but we should recognize that these surgeons are not always following these people routinely.

What are the national recommendations for monitoring these people?[6]

It depends on how long out they are from their surgery. In the first 3 months, they are almost always monitored by the surgeon. However, we tend to inherit these patients as they migrate out from the surgeon, and if they are not in a Center of Excellence where they may be monitored on a routine basis.

Postoperatively, we routinely suggest that these people should be followed every 6 months, in particular for the first 3 years, and then once a year thereafter.

The chemistry profile would include not only a complete blood cell count (CBC) but also lipids, ferritin, zinc, copper, magnesium, vitamin A, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, folate, whole-blood thiamine, and vitamin B12, and then 24-hour urinary calcium. These are things that we do every 6 months for the first 3 years and then annually thereafter.

In conclusion, what I want you to remember is that this is a lifetime monitoring requirement. It is not being done enough, even though it is incredibly important. Patients need to be proactive if their doctor is not doing it. I do not care if you are a primary care doctor, a gastroenterologist, or whatever—make sure that these patients are on the chewable vitamin twice daily, that they are on the respective elemental calcium, and that they are monitored on a regular basis. It is a lifelong requirement, with catastrophic potential otherwise.

I hope this helps you in your next interface with these patients. Take every sign and symptom (eg, neurologic, visual, dermatologic), and keep monitoring. Look for such things as anemia or edema, or something as simple as hair loss. These are all important facets. Take every symptom and sign as potentially related to the gastric bypass and micro- and macronutrient deficiency.

I am Dr David Johnson. Thanks again for listening. See you next time.

Comments