Susan B. Yox, RN, EdD

Director

Editorial Content

Medscape

Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP

Executive Editor

Medscape

Laura A. Stokowski, RN, MS

Senior Editor

Medscape

Loading...

Susan B. Yox, RN, EdD; Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP; Laura A. Stokowski, RN, MS | August 26, 2015

Parental refusal of immunizations for their children is a problem faced by most pediatric, family practice, and public health clinicians. According to a survey conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP),[1] 7 of 10 pediatricians reported that a parent in their practice had refused an immunization for a child in the preceding 12 months, a stance known as "vaccine hesitancy."

Vaccine hesitancy is defined as "a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services."[2] Parents offer many justifications for declining vaccines for their children and are not easily persuaded by statistics about a vaccine's safety and efficacy, or horror stories about children who developed a vaccine-preventable disease. The burden on clinical practice can be significant, and clinicians must wrestle with such questions as how to provide quality pediatric care, how to protect other patients in the practice, and how to protect their own liability for any poor outcomes resulting from continuing to provide care for unvaccinated children.

Image from iStock

In the first seven months of 2015, measles was reported in 173 US residents from 24 states and the District of Columbia.[3-5] Most of these cases (64%) were part of a large multistate outbreak linked to an amusement park in California.[3-5] This followed a record number of measles cases (668) in 2014.[5] According to provisional data, as of July 24, 2015, approximately 17% of US residents who contracted measles were confirmed to have been vaccinated against measles, but only about 8% had received at least two doses of the MMR vaccine. (CDC communication; August 19, 2015)

On the heels of the California outbreak, sporadic news reports claimed that more parents (including some who had previously refused vaccines) were seeking and accepting vaccination for their children,[6] and Merck sales of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine soared.[7] It is unknown, however, whether clinicians across the United States have experienced any real or lasting changes in vaccine acceptance among parents of children in primary care settings. Medscape conducted a survey of vaccine providers to find out.

Image from iStock

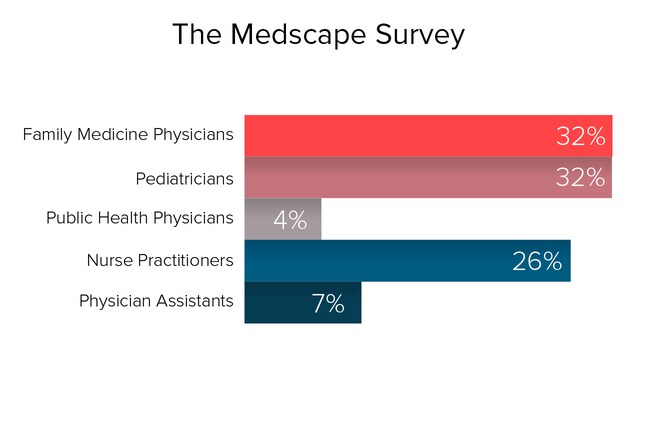

In July 2015, we surveyed 1577 physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in pediatrics, family medicine, and public health. Only those clinicians directly involved in vaccine care, either by prescribing/administering vaccines to children or developing vaccine policy, were included. Of the respondents, 58% were women and 42% were men. Practice locations were in the Northeast (14%), Mid-Atlantic (19%), Southeast (16%), Great Lakes (16%), South Central (8%), North Central (5%), Southwest (6%), Northwest (4%), and West (14%) regions of the United States. The survey questions sought to determine the perceptions of these clinicians about vaccine hesitancy in the aftermath of the 2015 measles outbreaks. The margin of error for the survey was +/- 2.46% at a 95% confidence level. (Please note: Totals do not always equal 100% due to rounding and because many questions allowed respondents to choose more than one answer.)

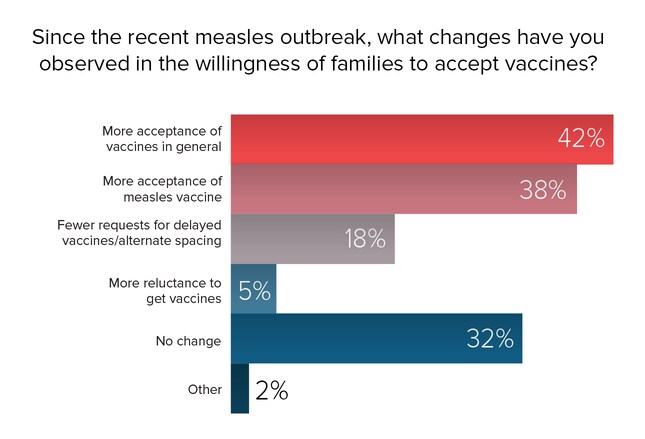

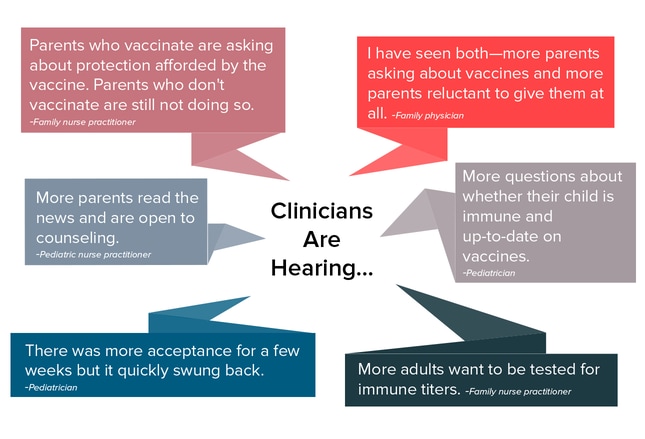

According to the respondents, recent measles outbreaks have induced more acceptance of the measles vaccine and, in fact, vaccines in general, in at least some parents. Parents' fears about their children contracting vaccine-preventable disease is the driving force behind this greater acceptance, although admission to school, daycare, and camp and increased knowledge about vaccines are contributing factors.

Indeed, a survey[8] of nationally representative households taken after the 2015 measles outbreaks suggested that parental attitudes towards vaccines were shifting. A recent survey asked parents how their beliefs about vaccines compared with the views they had held a year previously. About a third, 34%, reported that they believe that vaccines have more benefit, 25% believe that vaccines are safer, and 35% of parents report more support for daycare and school vaccine requirements.

Despite these signals of increased acceptance, at least 1 in 3 clinicians in our Medscape survey have not perceived any recent changes in the willingness of parents to accept vaccines for their children.

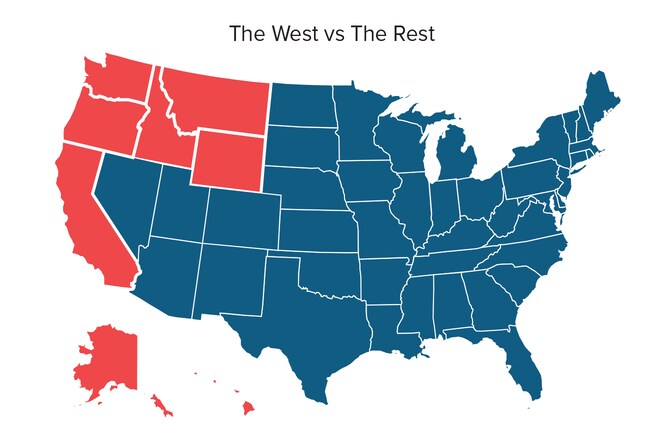

To examine whether geographic proximity to the California measles outbreak disproportionately influenced parents' attitudes towards vaccines, survey results were analyzed by region. More providers in "western states" (West and Northwest regions combined) report an increase in acceptance of the measles vaccine (46% in western states vs 36% in rest of country), as well as vaccines in general (51% western vs 41% rest of country). Fewer parents are asking for delayed or alternate spacing of vaccines (23% western vs 16% rest of country). Looking at it from another angle, fewer providers in western states reported "no change" in parents' willingness to accept vaccines (21% western vs 34% rest of country).

It is also possible that some California parents, having heard about the law to end religious and personal vaccine exemptions, are sidestepping admission denials to school or daycare by having their children vaccinated.

The fact that some of the people who contracted measles in the 2015 epidemic were vaccinated against measles was not lost on many parents. Even some of those who vaccinate their children began expressing more concern and skepticism about the efficacy of vaccines, and clinicians are receiving more questions than usual about the level of protection afforded by the measles vaccine.

For some clinicians, these questions seemed to correspond to the level of media attention about the measles outbreaks. Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, cautions that this bubble might yet pop. "For the first time, physicians are starting to see a backlash to the 2015 measles epidemic. Parents seem to be somewhat less interested in delaying or withholding vaccines for their children. And some parents are actually starting to get angry at parents who are choosing to put their children and others at risk. Furthermore, such states as California and Vermont have eliminated philosophical exemptions to vaccination. The big question is, how long will this last? Either we are seeing a true sea change in attitudes or we're seeing a momentary change based on a recent outbreak. Only time will tell."

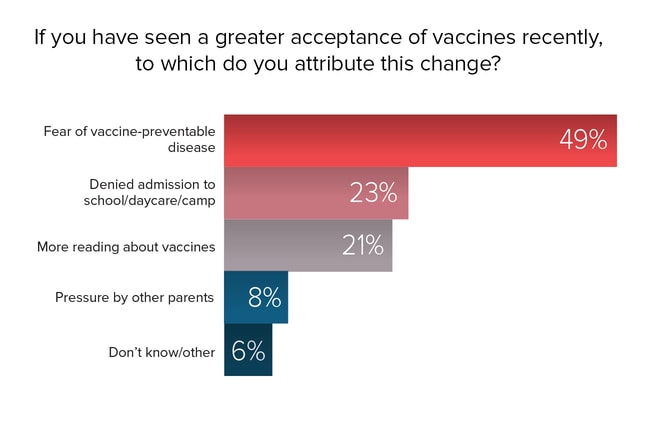

The measles outbreak clearly frightened many parents. Among clinicians who perceived higher rates of vaccine acceptance in recent months, almost half (49%) attributed the increase to parental fears about their child contracting a vaccine-preventable disease. Almost one fourth (23%) of clinicians reported that the recent increase in acceptance was the consequence of an unvaccinated child being refused admission to school, daycare, or camp. Another 21% of clinicians attributed the increase to parents reading more about vaccines and improved comprehension of the issues.

However, many clinicians credit the spike in media coverage about vaccine-preventable illnesses, including negative portrayals of non-vaccinating parents ("anti-vaxxers"), for bringing some previous refusers into the clinic requesting vaccines. The clinicians, too, have chipped away at vaccine hesitancy by repeating their advice at every encounter, dispelling myths and misunderstandings, and attempting to change parents' minds with facts and evidence.

Healthcare professionals in western states were significantly more likely to attribute the increasing acceptance of vaccines primarily to parents' fears that their children will contract a vaccine-preventable disease. Proximity to the measles outbreak drove home the fact that measles has not been eradicated, and children can be exposed literally in their own backyards. Some parents may have found it easier to refuse vaccines when they had never heard of a case of the disease, but with the rapid spread, and unknown source, of the measles outbreak at Disneyland, a risk that was formerly nebulous became real.

Image from iStock

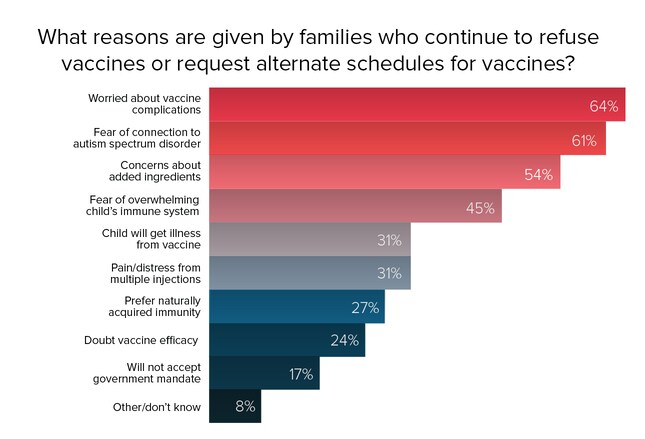

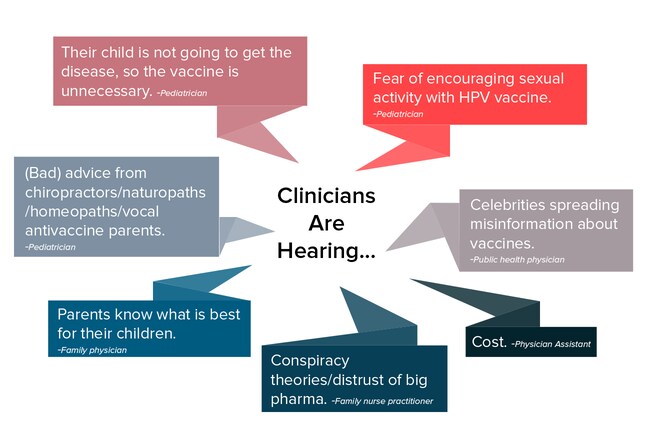

It comes as no surprise that clinicians are still hearing the most persistent misconceptions about vaccines (high complication rates, autism link, and dangerous additives) from vaccine-refusing parents. The widely held and enduring belief that giving vaccines (especially multiple vaccines administered simultaneously to very young children) overwhelms or somehow weakens the child's immune system[9] is at the root of another element of vaccine hesitancy: requests for alternate administration schedules (delaying vaccines or spacing them out more). Some clinicians are opposed to altering the recommended immunization schedules, whereas others view this as a reasonable compromise ("better than nothing") and a viable strategy for keeping the parents in the practice and engaged in the process of vaccination. Alternate schedules, however, are not evidence-based, and leave children susceptible to disease for longer periods of time. Not following recommended schedules also increases the chance that immunizations will be missed entirely.

Nanny states, civil liberties, big pharma, and conspiracy theories involving the government and the pharmaceutical industry have not disappeared from the vaccine conversation. Nor have preferences for "natural immunity," reliance on "good diets," or confidence that children will not be exposed to vaccine-preventable illnesses.

Many clinicians are familiar with the phenomenon known as "confirmation bias"—the tendency of humans to ignore or discount evidence that is contrary to their beliefs.[10] That confirmation bias is operating in the minds of some "anti-vaccine" parents is suggested by the experience of some of our survey participants, who reported that following the measles outbreak, a few vaccine refusers became even more adamantly opposed to vaccines, and some clinicians even observed an increase in the number of vaccine refusals. Many clinicians view it as futile to spend time trying to convince these parents that their beliefs are false; these qualms are one reason that some providers have adopted a policy of not accepting nonvaccinating families into the practice or asking them to leave if they fail to adhere to recommended vaccine schedules or agreed-upon alternate schedules.

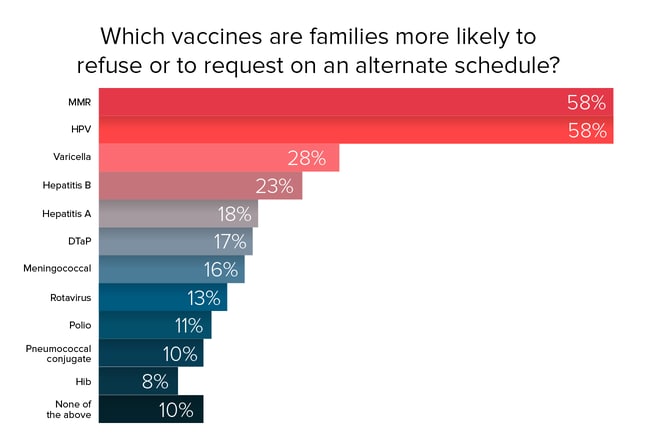

Heading the list of "most likely to be refused" in our survey are the MMR and HPV vaccines. MMR's reputation seems to have been permanently stained by the now discredited link with autism; the perception of a connection persists. After a major measles outbreak in the United Kingdom, more than half of parents of unvaccinated children who contracted measles cited a link with autism as the reason for refusing the MMR vaccine.[11]

Objections to the HPV vaccine reported by survey participants include the fear that giving the vaccine will encourage sexual activity, and the conviction that the child is too young for sexual activity and therefore does not need the HPV vaccine. Media reports about complications associated with the HPV vaccine pose other barriers to its uptake.

The AAP offers a handy resource that outlines the key points to make when addressing parents' concerns about specific vaccines.

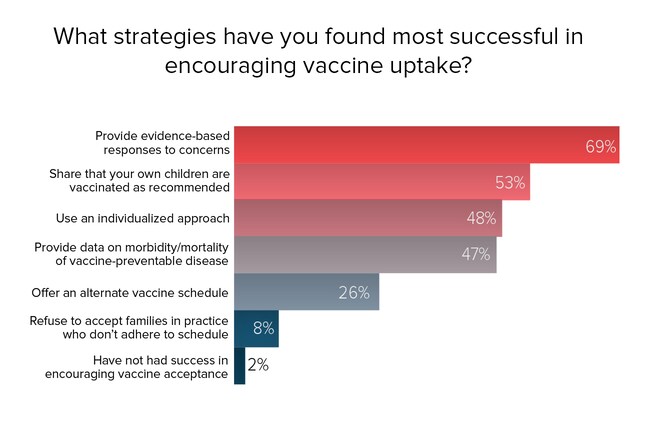

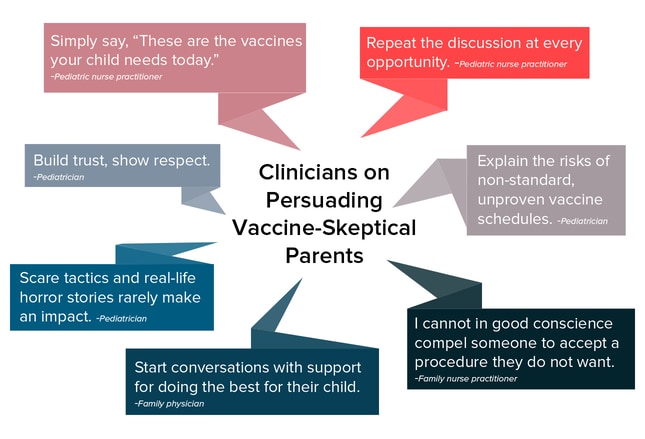

Asking parents about their specific concerns, and answering those concerns with the evidence, was the strategy deemed most likely to succeed by respondents. Sharing that the clinician's own children are vaccinated on the recommended schedule is considered another powerful method of influencing vaccine acceptance.[12] Confronting vaccine hesitancy is not a one-size-fits-all proposition,[13] and different strategies might work with different parents, as evidenced by the number of clinicians who take an individualized approach to this issue. Furthermore, a parent's concerns may differ depending on whether the child is an infant or an adolescent.[14]

Almost half of clinicians use the tactic of providing information about the disease that the vaccine is intended to prevent. Another one fourth offer alternative vaccine schedules when requested. Relatively few clinicians (8%), however, attempt to encourage vaccine acceptance by declining to allow vaccine-refusing families to remain as patients.

Building trust, showing respect for parental beliefs, and beginning conversations from the perspective of parents and clinicians both wanting to do what is best for the child are among the other strategies offered by respondents. Repetition and gradual acceptance are believed to be more effective than trying to change a parent's mind during a 10-minute encounter.

Clinicians were mixed on whether scare tactics were effective in changing parents' minds about immunizations. Some suggest telling parents about children who contracted vaccine-preventable diseases, whereas others believe that this has no impact on those who are set against vaccines. Repeated direct attempts to counter a parent's misunderstandings about vaccines might increase the potential for perpetuating those myths through repetition, thereby breeding familiarity and strengthening the memory of incorrect information.[10]

A recent study[10] compared two approaches to addressing the MMR vaccine-autism myth. One was direct information about the risks associated with measles (the disease-risk intervention), including images of children with measles, and the other was information about why the MMR-autism link is invalid (the autism correction intervention). They found that the disease-risk intervention was more effective in changing attitudes toward vaccination, but the persistence of these attitude changes is unknown.

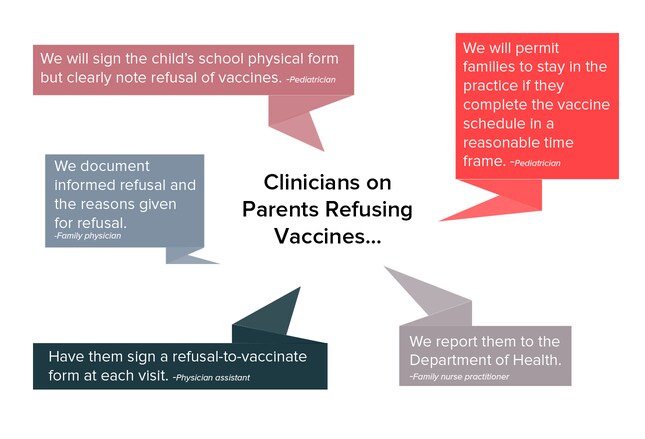

Many clinicians take a hard line toward vaccine hesitancy and do not permit unvaccinated children to remain in the practice, despite the fact that such policies are said to be misguided.[15] Some allow them to stay as long as they adhere to a catch-up schedule. Those who do allow patients to remain often do so because it affords an ongoing opportunity to try to convince the parents to accept vaccines for those children.

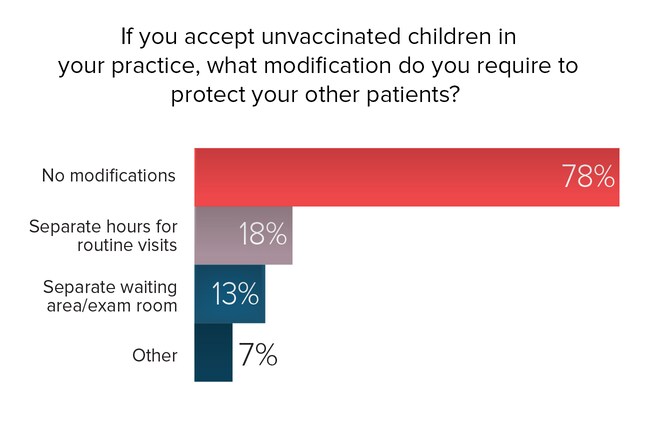

Most clinicians (78%) who allow unvaccinated children to continue as patients do not make any special modifications to protect other patients in their practice. Few practices have the space to offer separate waiting rooms or to have exam rooms set aside for unvaccinated children. Unvaccinated children who present with signs and symptoms of a possible vaccine-preventable disease may be asked to wait outside until called, or may be identified as quickly as possible and placed in an exam room, with a different exit to be used when they leave.

Providers described additional steps taken to protect other children in the practice, including having parents call ahead if their unvaccinated children need to be seen for a fever or rash and scheduling unvaccinated children's appointments at the end of the day.

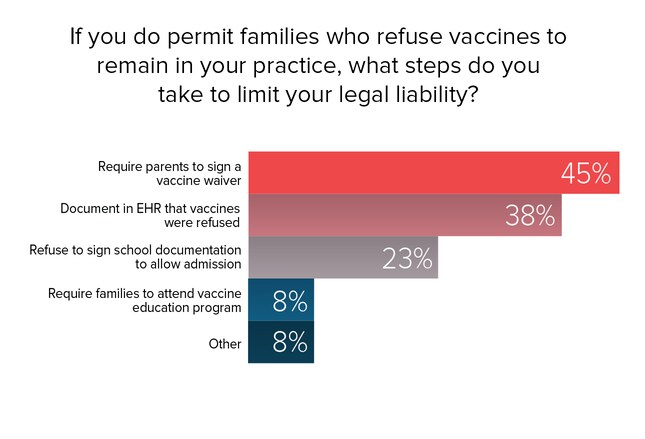

Clinicians who allow families with unvaccinated children to remain in the practice often worry about their own liability if the child contracts a vaccine-preventable disease or transmits it to others.

The most popular strategies to mitigate the clinician's liability are having parents sign a waiver of "informed refusal" of vaccines (often at every visit), and to document each attempt to educate and persuade parents to accept vaccines in the patient's electronic health record. About 1 in 4 clinicians will decline to sign any documentation (vaccine exemption form or school health/physical form) required for school admission for unvaccinated children.

Documentation of vaccine refusal should include these elements[16]:

Some evidence suggests that pediatricians are more likely than family practice physicians to require vaccine refusal forms.[12]

Consistent with AAP's recommendations, many clinicians confront vaccine hesitancy by trying to educate parents about the risks and benefits of vaccines, as well as the risks associated with remaining unvaccinated. Many offer educational materials or direct parents to reliable Internet sources for vaccine information. Evidence on the effectiveness of these efforts is mixed. Some studies find that brief interventions can encourage vaccine uptake,[17] whereas others find that these interventions can actually increase vaccine opposition in vaccine-refusing parents.[18]

According to the AAP,[19] however, continued vaccine refusal after adequate discussion should be respected unless the child is put at significant risk for serious harm (eg, during an epidemic of a vaccine-preventable disease). In those rare cases, state agencies might need to be notified to override parental discretion on the basis of medical neglect.

When all avenues have been exhausted, some clinicians will give families notice that they need to seek another provider. In general, AAP believes that providers should avoid discharging patients from their practices solely because a parent refuses to immunize his or her child.[19] However, when a substantial level of distrust develops, quality of care can be compromised, and families will be better served by finding another provider. Without this trust, vaccine hesitancy is unlikely to change.[20]

The AAP policy statement[19] recommends the following:

Image from iStock

Several recent studies suggest that healthcare providers are still the primary source of information about vaccines.[21,22] However, there is no question that the Internet and social media have played a huge role in enabling the growth of the anti-vaccine movement,[23,24] and depending on the search terms used, parents can more easily find myths about vaccines and anti-vaccine messages than evidence-based information about the risks and benefits of vaccines.[25] Many survey respondents encourage better use of social media to disseminate pro-vaccine messages.

Most also acknowledge the power of the personal approach, although time is insufficient to support this in daily clinic practice, and it doesn't work with all parents. One pediatrician in our survey said, "It seems the harder one pushes, the more the family rejects the vaccines. A personal relationship with the doctor seems most helpful, but peer pressure from vaccinating families helps too." A public health clinician emphasizes another aspect of vaccine responsibility, saying that we need "stronger advocacy for families to understand the social contract—their obligation to protect others to be protected themselves."

Previous

Next

Previous

Next

| 0 | of | 00 |