20 Years of Medical Practice

Dear Medscape Readers,

At this juncture of celebrating Medscape's 20th anniversary in online publishing for medical professionals, I thought it would be nice to look back at medicine's past as well as ahead to the future of medicine.

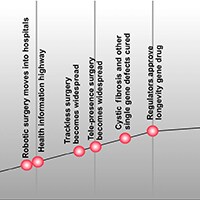

As I wrote about in The Patient Will See You Now, a graphic (Figure) published in The Economist in 1994, which was just around the time that Medscape was getting off the ground, has been stuck in my head since I first saw it. It portrays some pretty bold predictions about the future. As you can see, it accurately pegged the near-term use of robotic surgery and even anticipated some effective treatments, albeit certainly not a cure, for genetic disorders like cystic fibrosis.

Figure.

Source: Graphic designed for The Patient Will See You Now (Basic Books 2015), using information from "A Survey of the Future of Medicine" (The Economist; March 19, 1994). https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-15236568.html Accessed May 20, 2015.

Down the Pike: What the Future Holds

The Economist's prediction that we'll have a longevity drug by 2020 seems much too optimistic. But the fact that there are multiple companies—like Calico and Human Longevity Inc. —now intensely pursuing this objective with extensive financial support makes it a bit more plausible. In recent years there has certainly been an enhanced understanding of the science of human aging, and this will probably accelerate efforts to extend human lifespans. Perhaps someday in the next 20 years this concept of a longevity drug will be actualized.

Still, the idea that most diseases will be cured and that life expectancy will jump from 85 to 100 by 2040-2050 looks especially rosy. Because there are so few true cures in medicine, it's hard to think that there will be an exponential increase in this short time span.

On the other hand, I do think we're in for some radical improvements in preventing conditions and diseases that have "attack" characteristics, like heart attacks, strokes, seizures, asthma, and autoimmune diseases. Using omic tools like DNA sequencing or RNA tags, we'll be able to identify individuals at high risk for certain diseases. Wearable or embedded biosensors could be used to continuously monitor individuals well before signs, tissue destruction, or a clinical crisis develops. This will involve contextual computing and deep/machine learning for the individual. And, in the years ahead, it should be feasible and increasingly practical to track large cohorts of people with conditions of interest. As a result of tracking these large cohorts, one or more of these conditions will become preventable in the next 20 years.

As for cancer, a revolution is already underway using the liquid biopsy (blood) sample instead of, or in addition to, a tissue biopsy. This new window into the cancer dynamic process will ultimately be used for both tracking a patient being treated for cancer and, eventually, for making the diagnosis in patients. That's why Steve Quake and I wrote "A Stethoscope for the Next 200 Years" in the Wall Street Journal earlier this year. This new stethoscope sees inside the body at the molecular level with the newfound capability of looking into an individual's biology to know whether a person is in the early stages of developing cancer. That certainly will change what we think about as an annual "checkup."

Another future hope is in the area of Alzheimer's prevention. Using auto-antibodies derived from cognitively intact elderly individuals, the pharmaceutical company Biogen has seen some strong initial evidence that antibodies can be used to go after beta-amyloid years before it starts forming the neuron-choking plaques that cause Alzheimer disease. This research is promising in that someday we may get over the fixation on the "C" (cure) letter and move to the "P" (prevention) instead.

Of course, these futuristic notions are simply that right now—future ideas that need to be fully developed and validated. I have deep concerns about the potential for false positives and the issues of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, which have been nicely articulated in the book Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health (Beacon Press, 2011) by H. Gilbert Welch, Lisa Schwartz, and Steve Woloshin, and by Atul Gawande in his New Yorker article, "Overkill." So we are a long ways off from these potential advances; nevertheless, just being able to "see" the possibilities is enthralling. One thing for sure: 20 years from now (and hopefully sooner) we won't be saying "precision medicine," "personalized medicine," digital medicine" and "genomic medicine"—it'll just be "medicine." And Medscape will be there to cover it.

Best regards,

Eric J. Topol, MD

@EricTopol

Editor-in-Chief, Medscape

PS – Check out Medscape's special series commemorating its 20th year.

Medscape © 2015 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Topol: 20 Years Down; What's in Store for the Next 20? - Medscape - May 27, 2015.

Comments